War Crimes in Bucha and Criminals on VKontakte

Open Measures investigated VKontakte for information on potential war criminals in Bucha, known as the “Despicable 10”

TLDR

At Open Measures, we have been archiving data from VKontakte, known as the “Russian Facebook,” on a massive scale. After filtering data from nearly 40 million users, we found the profiles of 700 Russians, among them nine of the ten soldiers accused of committing war crimes in Bucha, Ukraine (known as the “Despicable 10“). In collaboration with Invader.info, we also found the likely identity of their driver based on many converging indicators.

VKontakte stores a wide range of highly-detailed personal information. As such, it is an invaluable resource for OSINT professionals to unravel and document ongoing crimes. Open Measures aims to use its data to support an ongoing ICC probe into the war crimes in Bucha. We will also support Iryna Venediktova, Ukraine’s Chief Prosecutor, and the Bucha Prosecutor’s Office in their investigations.

In this report, we outline our data, methods, and critical initial findings with the goal of empowering researchers, war crimes litigators, and archivists to expose more of those potentially responsible for war crimes in Bucha. Our matched profiles are available in this Cryptpad (contact us if you have trouble accessing them).

Our matched profiles can all be found in the following locations in this Cryptpad or the file attached to this post (please contact us if you have trouble accessing them).

What is VKontakte?

VKontakte or “VK” (ВКонтакте) is a social media platform founded by Pavel Durov in 2007. It began as an invite-only platform aimed at universities, earning it some comparisons to Facebook. Durov has a complex history, which includes a stand-off in St.Petersburg and a self-imposed exile after his dismissal as CEO of VK. His phone number was also found in the Pegasus spyware leak.

According to the company’s website, VK has 97 million users per month. Wikipedia shows VK had at least 500 million users as of Aug. 2018. Other than Odnoklassniki, VK is one of the last social media networks not blocked in Russia. As reported by Wired, VK has experienced significant user growth from the ban on Facebook since Russia invaded Ukraine.

Though VK originally claimed to promote free speech, the platform has since hired several government-friendly executives. Since then, the site has cooperated with government censorship and arrest requests. One arrest request came as a result of a post that read, “No war in Ukraine but a revolution in Russia!”

On March 20, VK was hacked and its users were sent messages about the invasion in Ukraine. Messages included information about civilian deaths and Russian military and economic losses. Additionally, the messages threatened that Interpol would use personal data on VK to arrest anyone supporting the invasion.

Prior Research

Shortly after Putin started the war in Ukraine, which politicians and journalists have called a violation of the Genocide Convention, Open Measures published a report opposing the Kremlin’s revanchism. The post shared a list of Telegram channels and revealed our new server for searching archived media. Using these tools, we called for further investigation into ongoing war crimes.

Shortly after, we published another report outlining the information war aspect of the conflict, which was flourishing on fringe platforms like Telegram. Shortly after, we began crawling specific VK groups and pages as well to supplement these findings.

Russian soldiers and assets (such as “deniable forces” and “little green men”) have been notoriously lax about posting on VK – many have posted evidence of possible war crimes as well as other critical intelligence. This lead in part to the “Bellingcat Bill” pushed by the Kremlin, criminalizing soldiers’ cell phone and social media use.

VK has been home to a range of bad actors, partly as a result of lax moderation against right-wing extremism. International white supremacist networks such as the KKK have sought refuge on the platform (from moderation on platforms like Facebook).

Various OSINT practitioners have verified numerous alleged war crimes on VK, through tactics involving facial recognition software and phone data. While living in Russia, Rinaldo Nazzaro, the head of the white terror network The Base, was notably exposed as result of photos from his wife’s VK account.

Additionally, VK has become a battleground of the war itself, with activities ranging from debates to actual orchestration. A recent exposé by Reuters connected numerous alleged Bucha war criminals to online posts. These factors have made VK a treasure trove of OSINT leads.

Summary of Open Measures Data

Open Measures’ data collection methods on VK, both automated and manually-curated, began with processing every VK group mentioned in our Telegram data before soliciting our community for requests. This eventually led to pulling user profiles (and in select cases, their posts).

Our user profiles list included 112,833,873 users, though we only looked at those suspected to be members of the military who were involved in alleged war crimes in Ukraine (or close to those involved). In total, Open Measures currently has 91,259,864 posts from 3,756,385 unique accounts, drawn from approximately 14,500 targeted groups.

Our research focused on soldiers from the 64th Separate Motorized Rifle Brigade of the 35th Combined Arms Army. These soldiers were known to have deployed in and around Bucha, according to The Main Intelligence Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine. The soldiers were selected as a result of their actions in Bucha, which Putin later honored them for.

To expand our user list, we also collaborated with Invader.info, a project created by a Ukrainian-born data scientist. The partnership made use of novel methods for analyzing and crawling the data. Finally, we supplemented these methods with OSINT techniques, which are outlined further below.

Identifying User Trends

Age Distribution

In total, Open Measures has three types of VK data: groups, user profiles, and posts. The app and API only make posts public at this time, but they contain information about users and groups.

Officially, VK says they have over 90% of the Russian internet audience. We used age and gender information to estimate VK’s total users, as both fields are required when signing up for a VK account. Though users also need to enter a birth year, they aren’t required to display it on their profiles.

Of over 500 million accounts, only 395 million opted to share their birth year. However, by querying age range information through VK’s API, we found a number close to the one VK reported: a total of 510 million users.

The site also requires gender to be specified as either “male” or “female.” Using a similar querying method, we found about 218 million female accounts and 281 million male accounts (for a total of 499 million, another estimate of the total number of accounts on VK).

Users by Country

As of June 2022, over 232 million users had Russia listed as their location in their profiles. Likewise, 49 million listed their location in Ukraine. In 2017, the Ukraine banned VK to decrease Russian influence and move towards the West.

Still, despite some reported exoduses of Ukrainian users, the site was still used frequently. After a second exodus, the remaining VK users in Ukraine shifted towards pro-Russian and anti-Ukrainian rhetoric.

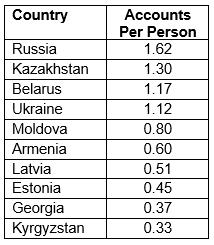

Some countries, like the United States and Brazil, are in the top 10 as a result of their large populations. To measure the smaller countries’ usage of VK, we adjusted for population to find the number of accounts per person, pushing some countries like Brazil further down the list.

Some countries that were initially high on the list fell to the bottom. For example, the United States has the fifth most VK users but only 0.02 accounts per person when adjusted for population. The countries with the highest rate of accounts per person are all in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

Finding Possible War Criminals on VK

Methods

Though Open Measures has its own data and tools for researchers to use, VK also has robust search features to find people, posts, communities, music, videos, classifieds, store products, and clips. For searching people, the options include region (country and city), school, college or university, age, gender, relationship status, personal views (religion, life priorities, important qualities in others, smoking and alcohol), company and position, military service, and birthdate.

Some user searches are restricted; performing a search for military service does not yield any results, but it is still visible on user profiles and searchable in our user profile data (or in the user profiles of our public post data on the API). Obviously, name, birth date, and military service were of most utility to our investigation.

We could then match users based on aspects such as name, birthdate, military position, and home city. This can been done manually – providing maximally accurate results but requiring much more volunteer effort to scale – or via automated code queries with complex rules for gauging the likelihood of a match.

When manually searching for a soldier on VK, we generally used the following procedure:

Search by name + date of birth (DOB) MM/DD, then open all profile links and rule out the profiles listing incorrect birth years.

DOB year is not required for a VK profile, so if you first search by MM/DD/YYYY, you might be missing valid profiles.

Younger kids might also make accounts before they are old enough (14 is minimum age), so the birth year may be off by one or two years despite having the correct MM/DD.

But for more common names, searching through every MM/DD profile is very time-consuming, so searching for name + DOB MM/DD/YYYY might be more productive.

Use passport city for additional narrowing-down and verifying correctness of findings. If the profile matches the birth year, this is less important, but if you only have MM/DD it’s a good way to check findings.

Though it’s not directly searchable on VK, military service listed in the account profile is another good indication that you’ve found a good profile. However, given the abundance of user profiles we scraped, we could also just search over the “occupation.name” field for users claiming to be in units of interest.

For example, looking into regiments accused of war crimes, 18 users self-reported being in the infamous 64th Brigade with the Military Number 51460; 10 users from the 76th Guards Air Assault Division (Unit 07264), and eight in the 234th Airborne Assault Regiments (Unit 74268). All were previously awarded for the occupation of Crimea, and were connected to alleged war crimes in Bucha by the New York Times.

All of these accounts are archived and documented, but these methods can be replicated on other units in the Russian offensive.

Another interesting method is just searching the unit number (ie в/ч 51460 for the 64th) in VK. You will often find public groups with members who have recently posted. Additionally, you can search in “videos” and find some that are very recent and worth downloading.

As part of this effort, Open Measures was proud to collaborate with the Invader.info project, which tracks social media profiles, network contacts, and images of Russian soldiers occupying Ukraine. The project’s methods and goals are outlined in detail here.

Using the described methods, Open Measures connected individuals involved in the invasion to their VK profiles. Confirmations of birth date, name, position in the military, home city, and other fields provides further evidence that could be used in war crimes trials, especially in conjunction with images showing faces in both locations.

War Crimes in Bucha and the “Despicable 10”

We connected 700 VK profiles to members of the infamous 64th Separate Motorized Rifle Brigade of the 35th Combined Arms Army, who seemed potentially connected to war crimes in Bucha, dovetailing with other related efforts to identify and archive such as this from Inform Napalm. Working with our partners, we assessed with reasonable confidence that we had identified nine out of ten of the “Despicable 10” from the attacks on civilians in Bucha.

Through name and birthday, we identified matches with other information wherever possible as well. These IDs can be found in the Despicable 10 tab of our matches spreadsheet.

From all the Despicable 10 accounts, we crawled 2,057 unique public posts. The most publicly active of them was Сергей Пескарев, with around 1,600 posts. Next was Григорий Нарышкин, Алик Раднаев, and the Sergeant, Никита Акимов (Nikita Akimov).

Nikita’s posting behavior reveals little of interest, except that he has a Twitch and Skype account used to post many kawaii anime pictures. He last accessed the VK accounts we tracked on April 28, 2022. His corresponding Telegram account informs us he was “last seen a long time ago.”

Using the images of the 10, we have further verified the accounts. For example, Nikita Akimov’s face is similar across two profiles we identified and the photo provided by the Defense of Ukraine. By comparing them, viewers can note the distinctive curve of the nose:

Of the Despicable 10, the majority listed cities in the far southeast corner of Russia closest to China. None came from anywhere near Ukraine.

Most of these Despicable 10 accounts had “last seen” dates up to the moment the invasion occurred – this would make sense, since Russian soldiers are not supposed to bring devices. However, four of the accounts show more current last seen dates (as of June 10, 2022). This means that they, or someone with access to their accounts, are continuing to access VK’s platform during the war.

As such, other individuals may have access to their phones. If the Despicable 10 had brought their phones themselves, they would have essentially become tracking beacons to the Ukrainian government.

These are the four recently active accounts:

Interestingly, Corporal Semen’s page changes his profile picture between May and June, from one showing his face to one obscuring it (possible to read as a subtle acknowledgment of potential guilt).

In one profile, he listed his political views as “monarchist.” Additionally, his listed phone number in the VK login goes directly to a 2FA prompt to the same number, suggesting that some account is using that number for login. Further research suggests that the number has not been connected to a network in some time. As a result, it is uncertain who, if anyone, is controlling it (or how).

While we hope to continue to support efforts to archive and identify potential war criminals, we rely on the broad expertise of those who read our work. These leads are just the beginning of what is possible from this data.

Facial Recognition and the Unknown Driver

Utilizing facial recognition is one of many different ways to leverage this preserved data. For example.

Trials run with facial recognition tools against the image of the as-of-yet unidentified photo of a Russian military truck driver featured in an investigative New York Times article suggests a match to Private Оломский Богдан Юрьевич (Bogdan Olomsky) of the 64th Separate Motorized Rifle Brigade of the 35th Combined Arms Army (OAVVO).

If these findings are accurate, the information suggests that the 64th Regiment, in addition to the 104th and 234th Airborne Assault Regiments previously reported, were present on 144 Yablunska Street in Bucha between March 3– 5.

Automated methods found five profile matches for Bogdan (1, 2, 3, 4, 5). All these profiles share the same name and city and have similar face photos at different ages. Four of the five profiles list the same birthdate in addition to sharing the same name, city, and similar face photos.

Running facial recognition experiments against the alleged war criminals in the New York Times article returned positive results for all five accounts. Based on their content, all of these accounts also seemed to be run by Bogdan.

One of Bogdan Olomsky’s VK accounts even lists the military unit (51460) he allegedly served with between 2016 and 2019 – the 64th Separate Guards Motor Rifle Brigade, who murdered hundreds of civilians in Bucha. In one of his profiles, he lists “kindness and honesty” as among the most important things he values in others and appears to have a “one love” tattoo on his wrist.

Findclone.ru is the standard for paid VK face searches, but users can also use open libraries (as done by invader.info). However, open libraries may provide false positives. As such, they must be supplemented with additional refinements, such as birthday, city, and military unit (if listed in the profile). Manual facial feature matching is necessary as well.

When the New York Times articles ran, we found five positive matches to Bogdan in our database of Russian military user profiles, further supporting the existing reports. Numerous facial features match across the images, including the round outer edge of the ears, the shape of the nose, lips, and eyes, complexion, and the length of the face.

One obstacle to facial recognition is that high-quality, unobscured images are harder to find in war footage (which is often grainy). However, the examples below show what is still possible even given these constraints.

Additional Leads

Radio Svoboda

One of the accounts we found posting often was “Донбасс.Реалии”. This translates to “Donbass Realities,” a project of Radio Svoboda / Radio Liberty. Radio Svoboda is itself a branch of the US Agency for Global Media, which was born out of the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG).

Though claiming independence, there have been numerous scandals regarding this agency’s past and ongoing relationships with the CIA and information warfare more broadly. Regardless of its true degree of independence, its active involvement in the Donbass information landscape on VK is as obvious as it is interesting.

Community Groups as War Fronts

Another unusual set of accounts are community group-like pages with a pro-Russian bias for occupied areas (found on VK, OK.ru, Telegram, YouTube, and Instagram). They follow a stylistic and functional pattern across accounts (e.g., My Krasnodon and My Luhansk).

These pages became more political as the war progressed, posting images of pro-Russian soldiers with heavy weapons and links to interviews with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. The pages now post “updates from the front” alongside similar content and engage obliquely in war-related efforts:

We found many interesting things in our preliminary research, but there is much more to uncover.

Using Open Measures Tools

A sample of 50 posts from Open Measures’ VK data can be viewed via the Search tool. This query searches for the term “Украина” (Ukraine). We can use the Timeline tool to get a sense of the discussion of the same term. Doing so reveals a peak in posts on Feb. 25.

To get a sense of where these VK users are getting their information on the conflict, below is an overview of the most-shared links in posts mentioning “Украина.” Note here that .su (Soviet Union) is a common Russian country code and top-level domain, so the majority of links shared are Russian websites.

Users can investigate the accounts most discussing Ukraine more deeply with our Activity tool to prioritize and isolate influencers.

To use our API to get specific sub-sections of relevant data, the first step is to get a general sense of the data – search for a word (here, “Украина”) with default settings, choosing VK as the site. This allows you to analyze the field names in the VK response JSON blobs. From the response, we can highlight two useful fields, [author] and [text].

Below is an example:

Below, we will show how to get the posts from a specific user, focusing on the most senior person we linked from the “Despicable 10,” Nikita Akimov. However, the same could be done to check for posts from any user of interest.

While Open Measures does not make our entire user profile collection public, the profiles of accounts we pulled posts for will be available in these API responses. To begin, we select the most recently active account of the two we matched (facial comparison between two profiles matches).

To get posts from a specific user, go to the interactive API docs page (or in your code), select VK, set [esquery] to [true], raise the post limit, and set appropriate values for the [since] and [until] variables (make sure [since] goes back far enough, in case a user hasn’t posted recently).

Then, in the term box write: [author : id560264474], where the author name is taken from the end of the user profile URL (in this case, https://vk.com/id560264474). The interactive API docs should look something like the below:

Useful Despicable 10 filter for the content endpoint of the API:

author : id560264474 or author : id120178883 or author : vyacheslav_2192 or author : id694659052 or author : id296316943 or author : id195711313 or author : id468252032 or author : id104618347 or author : id481580855 or author : id296489212 or author : id190451889 or author : id158829161 or author : id237447990 or author : id169306798 or author : id148528657 or author : id393553172 or author : id568512814 or author : id294615173 or author : id366951774 or author : id441355754These fields include a wide range of other interesting data, including geo-coordinates to military positions, Skype handles, and iPhone vs. Android use.

These examples give a sense of the range of possibilities for employing data to pursue leads related to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Conclusion

The VK platform serves as an interesting subject of research with a wide range of use cases. Users can look at the views of people allegedly responsible for war crimes, as well as further identifying information linking them to said crimes. We have also preserved all public metadata, which should be admissible in future ICC cases or those held in countries allowing the prosecution of foreign nationals.

As mentioned, we are gathering this information in the hopes of preventing violence and aiding various researchers and justice agencies in bringing bad online actors and potential war criminals to justice. To share your own insights, or if you have leads or ideas on how to further use this information, please contact us at info@openmeasures.io.

If you or someone you know is interested in translating this into Ukrainian, please reach out. A huge and special thanks from Open Measures to our research friends and community that quietly and humbly supported this publication.

Identify online harms with the Open Measures platform.

Organizations use Open Measures every day to track trends related to networks of influence, coordinated harassment campaigns, and state-backed info ops. Click here to book a demo.