Exploring the Online Presence of Syrian Armed Groups

Saraya Ansar al-Sunna and the Coastal Shield Brigade have made use of Telegram during their ongoing skirmishes in the region

TLDR

Saraya Ansar al-Sunna and the Coastal Shield Brigade are two competing Syrian insurgency groups formed after the Dec. 2024 fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime. They each have a presence on Telegram.

Open Measures analyzed both groups’ use of Telegram to share content and shape public perception.

Saraya Ansar al-Sunna, a Sunni jihadist group, have primarily threatened Shi’a Muslims and Christians online; the Coastal Shield Brigade, a Shi’a armed group made up of remnant Assadist forces, have threatened Sunni populations as well as Shi’a who cooperate with the transitional Syrian government.

Background

The Syrian civil war began in 2011 after the country’s repressive regime, then led by Bashar al-Assad, responded to citizens’ pro-democracy protests with lethal force.1 The internal conflict quickly evolved into a multi-pronged proxy war that saw involvement from international actors. More than 500,000 people died in the civil war and millions more were forced to flee the country before the Assad regime fell in Dec. 2024.2

Syria’s new government is led by President Ahmed al-Sharaa, also known as Abu Mohammed al-Jolani. Al-Sharaa formerly commanded al-Nusra Front, a militant Sunni Islamist group and al-Qaeda affiliate formed in 2012.3 In 2017, its successor group, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), formed, absorbing al-Nusra Front. Also led by al-Sharaa, HTS led the offensive that toppled the Assad regime. It is important to note that Assad is an Alawite, a subset of Shi’a Islam; opposition forces such as al-Qaeda and ISIS were led by Sunnis. As the nation’s new leader, al-Sharaa has sought to soften global perceptions, both of Syria and of himself, in ways that have angered his own zealous opponents.4

Since al-Sharaa toppled the Assad regime, a new wave of insurgent groups have formed in opposition to his government. Open Measures examined online networks associated with two such groups: Saraya Ansar al-Sunna (سرايا أنصار السنة) and the Coastal Shield Brigade, a subordinate group of the Military Council for the Liberation of Syria (المجلس العسكري لتحرير سوريا). The former is allegedly composed of HTS defectors and Sunni religious extremists and has carried out deadly attacks against minority communities throughout Syria.5 The latter includes former members of the Assad regime’s military and has attacked al-Sharaa’s government forces.6

Open Measures researchers used our research dashboard to better understand both groups’ origins, intentions, and communication strategies.

Methodology

To assess the motives and strategies of these new insurgencies, Open Measures researchers began by examining their official, publicly available Telegram channels. By tracing where messages from official channels originated and to what other channels they were forwarded (and by examining similar phrasing across channels), we were able to identify additional channels that likely have close affiliations or relationships with each insurgent group.

To assess how closely these channels interacted with one another, our researchers examined how frequently they reposted content from each insurgency’s official outlets as well as how similar and consistent their messaging was to the official messaging. To fact-check claims made in these networks about alleged offline events, Open Measures drew on the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED), a database of open source conflict events. After cross-referencing certain messages against ACLED, and with the help of researchers in Syria, our researchers verified as many of these claims as possible.

This report primarily focuses on Telegram activity between March 1, 2025 and Aug. 29, 2025, to capture the post-Assad transition marked by escalations of sectarian violence. Though Telegram’s policy of periodically removing channels and accounts perceived as extremist would typically be a research obstacle, Open Measures’ indexed collections allowed our researchers to fill in gaps in the record as needed, even for accounts and channels Telegram had already removed.

Insurgent Telegram Channels

Open Measures identified 12 Telegram channels that appeared to be closely affiliated with Saraya Ansar al-Sunna and five additional channels that frequently reposted content. Likewise, we identified four channels that seemed to be directly affiliated with the Coastal Shield Brigade and another three that frequently reposted their content.

Below, we will examine each network separately, comparing online and offline activities and offering assessments of each group’s political motivations. Since the outlets we found contained sensitive and sometimes unverifiable information, we have not made all names and identifiers in this research public.

Those interested in our full list of channels for further research can request it by contacting us at info@openmeasures.io.

Note: For clarity in the research below, now-defunct channels – i.e., those deactivated by Telegram or whose authors have stopped posting – are referred to as “former” channels. “Official” and “primary” refer to outlets verified as controlled by various insurgent groups. “Affiliated” refers to channels whose activity or content was closely related to the activities of official outlets, suggesting possible affiliation or coordination.

Analysis

Our researchers found that each group used different communication and content strategies to shape their public perception. While we made efforts to verify the claims made by each group, not all could be verified; likewise, each group’s intentions weren’t always entirely clear.

For instance, Saraya Ansar al-Sunna’s official and affiliated channels frequently mentioned anti-Christian sentiments and made death threats against Christian individuals and locations. However, only one attack against Christians has been widely attributed to Saraya Ansar al-Sunna.7 More widely confirmed are the group’s many strikes against Shi’a targets (with several recent incidents cited in the following section).

The Coastal Shield Brigade’s channels, on the other hand, cast themselves both as online representatives of the regional Shi’a diaspora and as victims themselves, through frequent humanitarian appeals to the international community. Despite the group’s ostensibly Shi’a-aligned stance, however, it still frequently targets and attacks Shi’a communities offline.

Saraya Ansar al-Sunna

To learn which accounts were amplifying messages from Saraya Ansar al-Sunna’s channels, our researchers traced the messages through overtly Shi’a-aligned Telegram channels (and through posts on X) by using significant keywords. On Telegram, Saraya Ansar al-Sunna makes Shi’a-focused threats, referring to them as “Nusayris” (an old name for Alawites) or “the Murshid sect.” The group also threatens Christians, whom they call “Nazarines” (نصراني) or “apostates” (مرتد).

Almost all Saraya Ansar al-Sunna channels we identified openly declared jihadist religious affiliations, frequently sharing long Quranic interpretations and death threats against nonbelievers, Christians, and Shi’a. While the group’s approach differs from traditional Islamic State media in its flexible usage of in-group jargon and the relatively low production quality of its videos, it shares certain themes and quotations with overtly propagandistic, Islamic State-run outlets.

For example, one channel shared a speech made by deceased Islamic State spokesman Abu Mohammad al-Adnani warning against Israeli incursions in Syria and cooperation with Western intelligence agencies; another declared support for the Islamic State-linked Free Masked Men Movement in Saudi Arabia. Both organizations have praised deceased caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as well.

Additionally, Saraya Ansar al-Sunna’s offline weekly magazine is titled “Dabiq Media Foundation,” the name and logo of which were both previously used by the Islamic State.

Online Claims for Attacks

On May 30, 2025, in a group Saraya Ansar al-Sunna uses as a public forum and message board, the insurgency threatened “individuals and entities of the infidel Nusayri regime” in Damascus, Damascus Countryside, Hama, Homs, Aleppo, Coast, and Dara’a – areas that had recently been taken over by al-Sharaa’s transitional government. Notably, this list excludes regions controlled by pro-Sunni forces, namely the government’s stronghold in Idlib, Kurdish-controlled Northeast Syria, and Druze-controlled Suwayda.

By June 13, 2025, the insurgent group claimed credit for the assassination of two Alawites in Homs.

On June 15, 2025, the group claimed responsibility for shots fired on the Sayyida Zeinab shrine in Damascus, one of the holiest sites in Shi’a Islam, and claimed credit for the June 22 bombing of the Mar Elias Church the day after the attack took place. The group also claimed responsibility for a prior shooting at the church on Feb. 21, though it remains unverified whether Saraya Ansar al-Sunna was actually responsible for both attacks.

Finally, on July 20, 2025, Saraya Ansar al-Sunna threatened specific Syrian businessmen, claiming they had “financed the Syrian regime during the war.”

Online Threat Spikes on Telegram

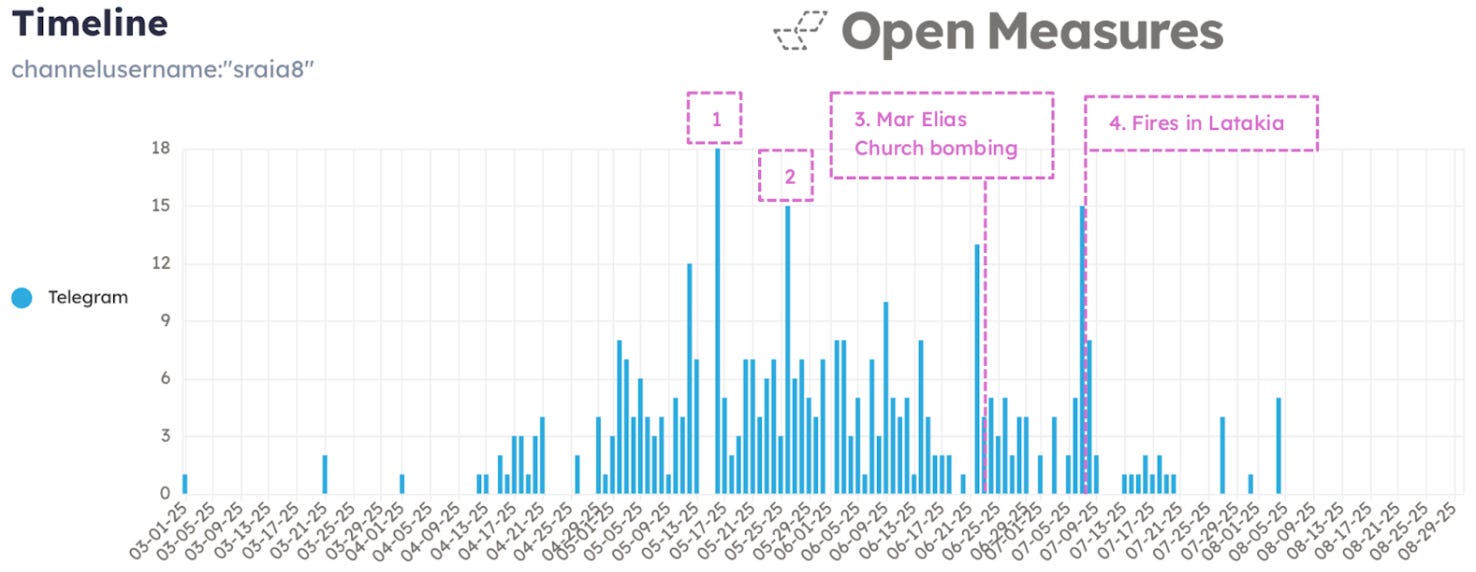

Activity spikes on Saraya Ansar al-Sunna’s main Telegram channel reflected spikes in online threats the group made that were not always correlated to verified instances of real-world violence.

The first activity spike, on May 16, coincided with a threat made on Facebook against Christians living in Homs. The second, on May 26, coincided with threats targeting a civilian in Damascus. The third and fourth spikes, on June 22 and July 7, coincided with various online activity related to the Mar Elias Church bombing and to extensive fires in the Shi’a heartland of the Latakia countryside, respectively.

Saraya Ansar al-Sunna also claimed credit for starting the July 7 fires in their weekly magazine; the Coastal Shield Brigade claimed credit for them as well. Some media outlets have suggested the latter claim was a fabrication,8 but neither claim has been independently verified by our researchers.9 Since only half of the largest online spikes were associated with real-world attacks, it may suggest that the group adopts an exaggeratedly bellicose stance online for other reasons that are difficult to confirm or verify.

Potential Origins and Allegiances

As yet, there is no journalistic or scholarly consensus about the demographics composing Saraya Ansar al-Sunna – namely, whether the organization is an authentic HTS splinter group (in whole or in part), an Islamic State front, an organic extension of Alawi uprisings on the Syrian coast, or another kind of entity altogether.10 11 12 While our research couldn’t definitively verify the group’s origins and intentions, our analysis pointed toward several possibilities.

Potentially supporting the theory of an independent Saraya Ansar al-Sunna were numerous messages that referred to the Islamic State as a separate entity. More ambiguous was a message acknowledging popular criticisms of Islamic State actions, as it went on to affirm the group as the successors of al-Qaeda.

Another message referred to Islamic State followers as “Dawais,” a pejorative term derived from “Daesh,” a transliterated acronym for the Islamic State with pejorative connotations in Arabic (for its sonic similarities to other Arabic phrases meaning “bigot” or “to trample down and crush”; these negative connotations have been warmly embraced by the organization’s enemies).13

Finally, in two separate interviews conducted by journalists via Telegram, two Saraya Ansar al-Sunna members denied the group had any affiliations with the Islamic State.14 15 16

Other Potential Affiliations

Notably, the most-recently created (but since deleted) account we identified in Saraya Ansar al-Sunna’s network focused on events in Tripoli, Lebanon’s capital. The channel, titled “Euphrates Now Reserve,” appeared to obfuscate its connection to Saraya Ansar al-Sunna.

Euphrates Now Reserve primarily echoed al-Sharaa government narratives and standard Syrian revolutionary talking points as well as extreme anti-Kurd and Druze sentiments. Their frequent mentions of separatism could suggest an interest in covertly influencing Syrians, particularly those in Lebanon and elsewhere in the diaspora.

Also possible are allegations that Saraya Ansar al-Sunna is a false flag operation designed to smear Sunni leaders and encourage public retaliation against their communities.17 As this is not verified, this claim could be investigated through further research.

The Coastal Shield Brigade

Our researchers tracked the Coastal Shield Brigade’s affiliates by looking at messages forwarded to secondary channels from the group’s primary channel. From our findings, the Coastal Shield Brigade’s content and communication strategies seemed to significantly differ from Saraya Ansar al-Sunna’s.

The group largely eschews the old guard iconography of Iran and Hezbollah, such as photos of figures like Hassan Nasrallah and Qassem Soleimani. Instead, it focuses on documenting the conflict and presenting certain facts as human rights violations, a kind of liberalized appeal for greater international influence.

Notably, Assad remnant-aligned groups have shared videos on Facebook of the July 7 fires in Latakia being celebrated by government forces with a caption implying that government forces started the fires intentionally. Though these groups are ideologically-aligned with the Coastal Shield Brigade, the specifics of their relationships are unverified (as are the veracity of the video and its associated claims).

More broadly, in-network posts on Telegram fell into one of three categories:

Direct threats, as exemplified by a Mar. 13, 2025, video of General “Abu Jaafar” Maqdad Fatiha, the Coastal Shield Brigade’s leader, announcing:

We have many prisoners in our custody. If you do not withdraw from the villages and stop your massacres and violations, we will take different actions. Roads will be rigged with explosives, and our fighters will move among you with silent weapons. Consider this a final warning.

Reports of missing and/or dead civilians – principally, disappeared Alawites who were kidnapped or killed along the coast. Many of these posts contained appeals to the international community to help protect Syrian Alawites.

Cautionary posts, often warning followers to avoid former Assadist military locations for fear of Israeli airstrikes.

Activity Spikes on Telegram

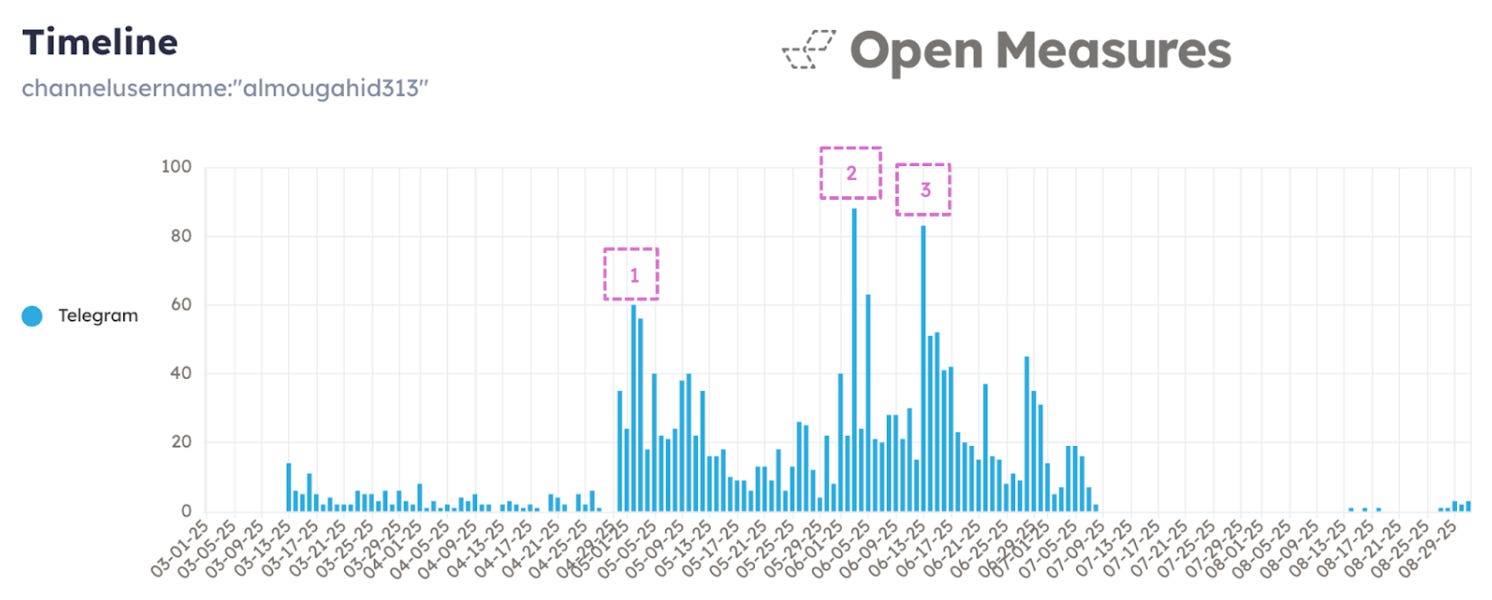

The activity spikes shown above were correlated with other events happening in the region affecting Alawites and regime-aligned individuals in Syria.

The first spike, on May 2, coincided with the beginnings of an uprising among formerly Assad-aligned Druze groups in southern Syria and an Israeli airstrike targeting Damascus.18 The second, on June 3, coincided with mass layoffs in state-backed jobs in the region that impacted Alawites. The third, on June 13, aligned with the beginning of the Twelve Day War between Iran and Israel (which affected Syrian Shi’a and Sunni populations alike).

A close analysis of these spikes and the shifting tone of messages over time suggests that the channel began as a forum for making threats but has since evolved into a platform for the Coastal Shield Brigade’s attempts at building solidarity with Alawites.

Conclusion

Both Saraya Ansar al-Sunna and the Coastal Shield Brigade have claimed credit for real-world harms and threatened citizens online; likewise, journalists and government sources have also attributed attacks to each group.

Though the groups’ activities have garnered significant media attention, they have successfully concealed many important details about their origins; in Saraya Ansar al-Sunna’s case, there is even some skepticism as to whether the group officially exists.

Uniting all the groups surveyed is a deep hatred of President al-Sharaa and his regime, a topic frequently mentioned across organizations. The consistent negative messaging could provoke al-Sharaa’s government to respond with harsh and extreme actions to maintain its control.

Today’s Syrian conflict is as much a digital war as a ground war, and it is also far from over. In the interest of helping researchers make sense of the conflict and to prevent the spread of misinformation, Open Measures will continue to provide updates on these and other conflicts.

Identify disinformation and extremism with the Open Measures platform.

Organizations use Open Measures’ tooling every day to track trends related to networks of influence, coordinated harassment campaigns, and state-backed info ops.

Sophian Aubin. “Syria war: Ten years on, Syrian Christians say Assad ‘has taken us hostage.’” Middle East Eye. 14 March 2021. Here.

David Ignatius. “Al-Qaeda affiliate playing larger role in Syria rebellion.” The Washington Post. 30 Nov. 2012. Here.

Ben Hubbard. “From Jihadist to President: The Evolution of Syria’s New Leader.” The New York Times. 25 Feb. 2025. Here.

Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi. “Saraya Ansar al-Sunna’ and the Damascus Church Bombing.” Middle East Forum. Substack. 25 June 2025. Here.

Kamal Shahin. “Forest Fires and Accusations in the New Syria.” 9 July 2025. New Lines Magazine. Here.

Raman Azad. “Ansar al-Sunnah . . . a reformulation dictated by necessity.” 2 July 2025. Ronahi. Here.

Cagatay Cebe. “Who is Saraya Ansar al-Sunna, radical group behind deadly Syria church attack?” Al Monitor. 14 July 2025. Here.

Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi. “’Saraya Ansar al-Sunna’ and the Damascus Church Bombing.” Substack. 24 June 2025. Here.

Sobhi Frangieh. “‘Ansar al-Sunna’. . . Who are they? And what is their connection to the bombing of St. Elias Church in Damascus?” Majalla. 26 June 2025. Here.

Patrick Garrity. “Paris Attacks: What Does ‘Daesh’ Mean and Why Does ISIS Hate It?” NBC News. 14 Nov. 2015. Here.

Abdullah Suleiman Ali. “‘Ansar al-Sunna’ is terrorizing Syria and declaring Sharia law an apostate. Our priority is minorities, and we plan to expand into Lebanon.” Majalla. 21 May 2025. Here.

Raman Azad. “Ansar al-Sunnah . . . a reformulation dictated by necessity.” 2 July 2025. Ronahi. Here.

Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi. “Saraya Ansar al-Sunna: Interview.” Aymenn’s Monstrous Publications. Substack. 24 June 2025. Here.

Ibid.